Neighborhood change is a critical issue for Baltimore, a city that is seeing strong revival in some areas and continuing decline in others, a city that is both racially and economically polarized. What happens in Baltimore’s neighborhoods, whether they are gentrifying or declining, continuing to struggle or growing in strength, not only matters deeply in terms of the quality of life and prospects of Baltimore’s residents, but also in many respects defines what kind of a city Baltimore is, and what kind of city its residents and leaders want it to be.

Our latest report, “Drilling Down in Baltimore’s Neighborhoods: Changes in racial/ethnic composition and income from 2000 to 2017” by urban researcher and author Alan Mallach, offers an overview of what has been happening in Baltimore’s neighborhoods since 2000—to what extent they have moved upward economically, moved downward, or stayed largely the same, and what that means in terms of population change, economic condition, and housing markets. The report finds that the largest single factor driving change in Baltimore is that Baltimore is losing its working- and middle-class families, but this trend plays out very differently across the city’s racial divide.

While Baltimore is losing both white and Black families, it is gaining a young, high-earning white population, but not Black population, through in-migration of families and individuals from outside the city. As a result, the white population is becoming more affluent, and the Black population poorer. This reverberates through the housing market. Where white millennials are moving, housing demand is strong and prices are rising. Where working- and middle-class Black families are leaving, housing demand is weak, prices are low, and abandonment is widespread. They are not the same neighborhoods.

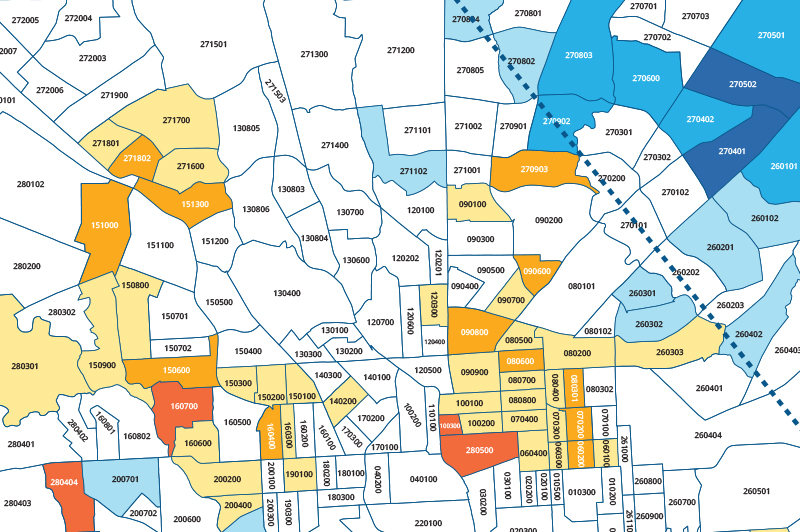

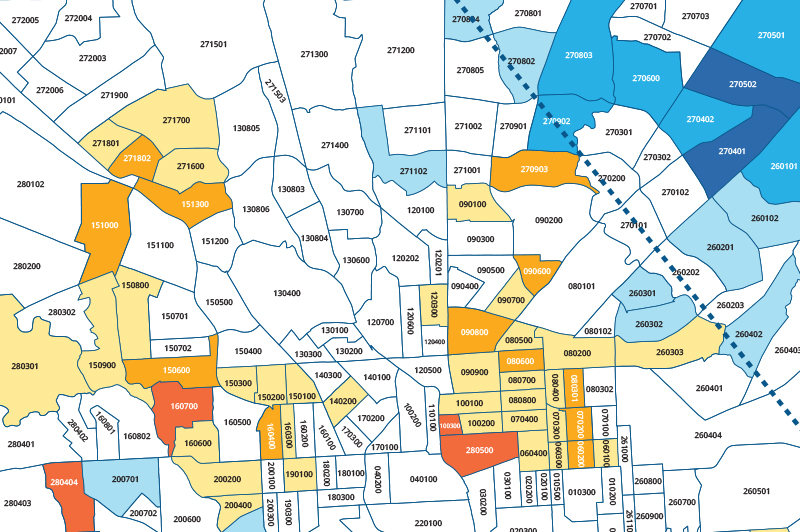

According to data from the US Census and the latest American Community Survey, out of 182 “potentially gentrifiable” tracts (neither upper-middle nor upper income in 2000), almost half of the predominately white tracts, but only 4 out of 110 of the largely Black tracts, actually gentrified by 2017.

While some of the findings in this report may be surprising and some may even be upsetting, the goal of this report is not to point fingers. The picture painted in the report in large part is a product of powerful and long-term changes in our nation’s demographic and economic reality, and reflects historical patterns of discrimination, segregation, redlining, and white flight. The ability of the city’s current community leaders and advocates to rapidly undo the city’s underlying social, economic, and physical challenges is severely limited. There are many things that can be done, however, to redress inequity, and the strategic framework recently adopted by the city’s Department of Housing and Community Development is a serious, thoughtful effort to begin grappling with many of these challenges.

The report lays out a picture of neighborhood change in a dynamic, beautiful, but deeply challenged city. In the end, it does not offer recommendations but does challenge public, private, and nonprofit stakeholders to ask themselves: “Why are working- and middle-class families leaving, and what can be done to change the conditions that are prompting them to leave?”